Palm Oil Production (Part 2), Challenges for Sustainability

Published by Anne Altor on Mar 26th 2018

Problems with palm oil evade simple solutions.

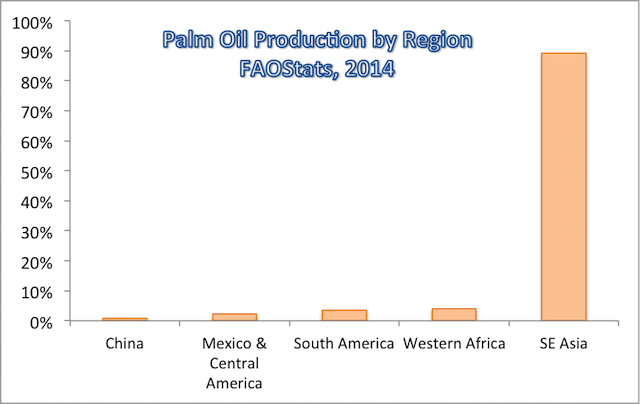

We may like to think that environmental and social sustainability problems can be solved in the marketplace by requiring responsible standards. While it's critical to work toward and support responsible standards, the way to get there is not always clear. This is clearly seen in the case of palm oil. The climate and soil conditions that are suitable for palm oil production occur in the most biodiverse areas of the planet, where rich rainforest and carbon-filled peatlands are found. Tropical forests worldwide are being systematically destroyed to produce palm oil, the number one source of deforestation in Malaysia and Indonesia. Despite sustainability initiatives in the public and private sectors, major deforestation for palm oil continues. Why has it been so hard for industry and government to establish sustainable palm oil production? I focus this post on Southeast Asia, especially Malaysia and Indonesia, where ~90% of global palm oil is produced (FAOStat). However, palm oil production uses significant amounts of land in other countries too. For example, in Peru, ~56 to 77 thousand acres were planted in oil palm as of 2014. In comparison, the extent of land under palm oil cultivation in Southeast Asia was 27 to 38 million acres.

Draining and destruction of peat swamp in Riau, Indonesia to establish a palm oil plantation.

Challenges to creating effective sustainability standards for palm oil.

There are many stakeholders in the palm oil industry. These include large plantation producers, smallholder producers (families or groups who cultivate oil palm on <50 hectares of land and who carry out a large percentage of palm oil production), processing mills, government and private enterprise, investors, trade regulating bodies, purchasers and consumers. Palm oil provides a major source of income for countries in Southeast Asia. Governments and industry in those countries don't always appreciate outside efforts to regulate how they use their land, especially when demands for sustainability are being made by countries that have already destroyed and exploited most of their own forest and other ecosystems (Noordwijk et al. 2017).

Global production of vegetable oils has increased exponentially since the 1980s,

and palm oil accounts for a large proportion of that increase (World Bank Group 2011). Why? Palm oil is cheap because the biodiversity losses and other costs involved are not accounted for in the price of the oil, and most of the production takes place in countries where labor rates are low. Palm oil is a saturated fat that doesn't require hydrogenation so has been promoted for food products and baked goods (World Bank Group 2011). The average oil yield per acre of oil palm is much greater than that of other major vegetable oil crops (Ser Huay Lee et al. 2013). In addition, palm oil has a wide range of edible and non-food uses; it's found in ~50% of foods in the grocery store, in cosmetics and soaps, and it's used as a biofuel. The World Bank, government and private investors have made significant investments in creating supply and demand for palm oil (World Bank Group 2011).

A forest fire in Sarawak, Malaysia. (Mattias Klum:Tierra Grande:AB, Washington Post)

Is the palm oil industry reforming?

In 1997, severe fires burned for months throughout Southeast Asia as a result of land-clearing to make way for palm oil plantations (Dudley 1997). These fires increased global attention on the problems with palm oil. Noordwijk et al. 2017 identify three phases related to efforts to stop the deforestation, land-grabbing and pollution associated with the palm oil industry. During phase I, international, non-governmental actors formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) in 2003, which initiated voluntary self-regulation of the industry. Some producers joined the RSPO in hopes of satisfying ethical concerns about the palm oil industry. The effectiveness of the RSPO at promoting sustainability practices in palm oil production is debated. I'll explore this in detail in a future post. In phase II, government initiatives were made in Indonesia and Malaysia to reclaim national sovereignty over palm oil production and regulation. These governments wanted to drive the process and saw international actors (the RSPO) as outsiders imposing on their affairs. They argue that they know best what is good for their citizens and should be entrusted to decide for themselves how to balance development and environmental concerns (Noordwijk et al. 2017). National initiatives included the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil initiative (ISPO) in 2009, and the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standard (MSPO) in 2013. In phase III, a "jurisdictional approach" emerged, where some local governments agreed to comply with RSPO or ISPO principles and criteria at the province or district level and connected these efforts to national sustainable development and climate change targets. However, the divide between "North and South" remains, and environmental concerns are pitted against arguments for economic development and national sovereignty in tropical countries (Noordwijk et al. 2017).

Is the palm oil issue that different from other patterns of resource consumption?

As the human population grows, we're mining the forests, hills, soils, lakes, seas and fossil reservoirs around the world. The problems with palm oil are mirrored in many other ecosystems and on store and pantry shelves. I'll continue to write about palm oil because I believe the issue is critical and that changes can and must be made. Also, consumer choices ultimately drive a lot of what happens on the ground. We are not fated to ravage every last piece of the web of life we're a part of. We need to find ways to live on this planet as participants in creating regenerative systems rather than destructive ones. Let's make the best of human creativity and ingenuity! You have important thoughts to add to the conversation. Please leave your comments below!

Supertrees in Singapore. Photo by Rod Waddington, wikimedia.org